Special Report

Investigation: How Roadside Foods Endanger Consumers’ Life With Trans Fat In Northern Nigeria

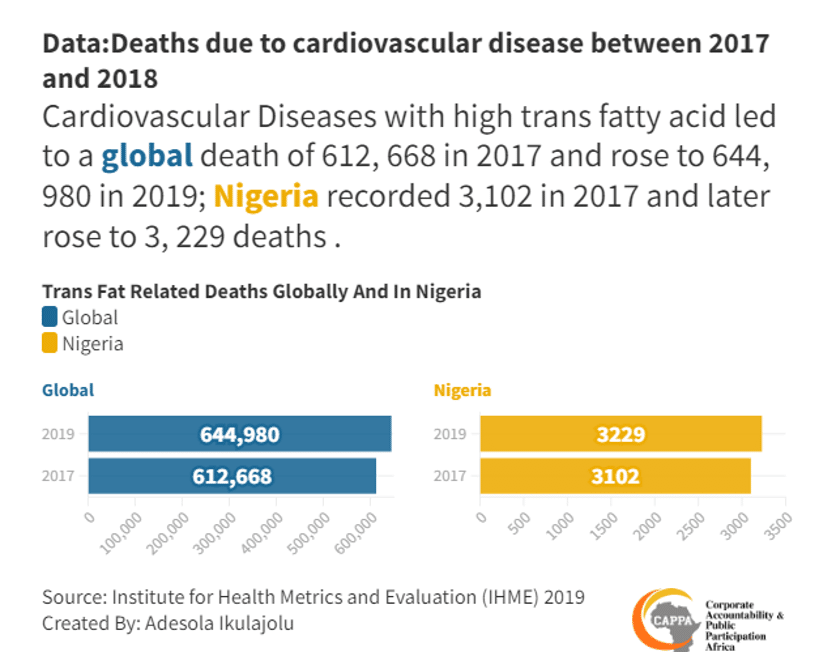

According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) Global Burden of Disease data 2019 (GBD) Result Tool), there was an estimated 854,000 deaths in Nigeria, of which 137, 000 were cardiovascular deaths and 3, 229 attributed to trans fatty acids (TFA)-related cardiovascular deaths. Trans fat which has been found to be present in cooking oil, including reused ones, is becoming a dangerous silent cause of death. In this report, ADESOLA IKULAJOLU visited Abuja, Nigeria’s federal capital, and two of the country’s most populous northern states – Kaduna and Kano – to examine the consumption of selected roadside foods and investigate their trans fat contents as it affects consumers’ health.

Abubakar Sani, in his late 30s, works as a commercial tricycle driver, plying the busy Jabi-Life Camp road in Abuja. Masa is a local northern Nigeria delicacy, made from maize or rice paste that is fried into bread roll-looking sizes, eaten alone or with a sauce. It is a readily available meal for Sani before work hours in the morning, and on his return home in the evening. It became his favourite from childhood in his hometown, Katsina.

“When I buy the masa in the morning, I eat it in my tricycle. Since I come out very early, I am unable to cook anything.”

Sani is neither bothered by the kind of oil used in preparing the masa nor by the reuse of the oil. The sweetness is what matters, not the health implications.

“Masa sweet and I dey eat am everyday. Na the oil dey give the masa better taste and nobody dey complain ” [sic] Sani said.

For Mama Ibo (as she prefers to be called), who sells kosai (akara or bean cake), making a profit is more her concern than the health risk of reusing the oil. ‘Kosai’ as it is called in Hausa language, is a popularly eaten food in northern Nigeria with no class distinction. In homes, as on the roadside, like at Mama Ibo’s, the oil is reused until it diminishes and is then topped up with fresh oil.

This is where Mama Ibo prepares her akara, fried yam and potatoes while attending to customers in Ibo road in Kano. Photo credit: Adesola Ikulajolu

The reused oil is never discarded. For four years, her open space has been besieged by commercial activities along the popular Ibo Road which connects to the airport and other major roads in Kano. Mama Ibo daily entices customers with the aroma of her Akara, puff puff and fried yam.

“I buy one new keg of cooking oil from the market every day to add what is left of the one I used the day before. I fry with it in the morning and in the evening,” she said, pointing to the already emptied unbranded 5-litre keg of oil near her.

Her customers include school children, teachers, office workers and drivers who begin to patronise her as early as 7 am as they head out and later in the evening. They are generally oblivious to the health implications of reused oil in preparing what they consider their favourite meals.

Cooking oil is a major ingredient in preparing roadside foods like masa, fried yam, suya, puff puff, fried fish and akara. Reused cooking oils have been found to be high in trans fat content which exposes consumers to the risk of Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs).

But do consumers like Sani know what trans fat is and the long-term effect of consuming it?

Both Sani and Mama Ibo said they are not aware that repeated use and reheating of cooking oil converts it to trans fat. The consumption of such oils increases the risk of heart diseases which the World Health Organisation (WHO) 2019 fact sheet on CVDs stated as the “number one cause of death globally.” This means that more people die annually from heart-related diseases than from any other reason.

In its report ‘Countdown to 2023: WHO Report on Global Trans Fat Elimination 2020,’ the global health body revealed how Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) are responsible for the death of about 41 million people each year. This is equivalent to 71% of all deaths globally, with CVDs topping deaths associated with NCDs. Research has also shown that increased intake of TFAs correlates with increased risk of CVDs which accounts for 16% deaths globally as stated by the Director-General of WHO, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, in the report.

Trans Fat, An Uncommon Threat To Health

Trans Fat also known as Trans Fatty Acids (TFA), is formed through the chemical process of hydrogenation of oils mainly used for domestic purposes such as cooking and frying. The hydrogenation process solidifies the liquid oil which makes it possible to increase the shelf life and taste of food products prepared with such oil.

C.K.O was 29 years old when he first suffered a heart attack. Unfortunately, two years later, a doctor confirmed him dead on arrival at the hospital, due to a second heart attack.

Dr. Onyenachi Charles, a medical doctor at the International Hospital in Kano, and cousin to C.K.O., narrated this incident.

He is now one of the over 150,000 Nigerians who are estimated to die from cardiovascular diseases yearly. This number is worrisome for a country without a TFA policy and whose citizens are also ignorant of the dangers in consuming foods high in trans fat.

Dr. Onyenachi who is a general practitioner explained how the regular intake of foods high in trans fat can cause heart problems leading to death.

She said, “Fats stick to the wall of the blood vessels causing it to become slimmer thus reducing the passage of blood flow to the heart muscles. For some people, it is as bad as almost little or no blood getting to the heart which then causes a heart attack because the heart muscle is starved of blood since the blood vessel is thickened by fats.”

While studies have shown that trans fats raise LDL (bad) cholesterol and lower HDL (good) cholesterol, trans fat in the blood contributes to the number of stroke cases globally and brain damage. Dr. Charles explained that when there is no flow of blood to the brain, it leads to stroke because thickened fats get dislodged to form “fat plaque” which then blocks the blood vessels from supplying blood to the brain. This becomes risky for consumers who don’t care about the cooking oil they consume.

More Risk For The Old And Young

For Hussein (not real name), a 10-year-old pupil in Kaduna, roadside puff puff is his favourite. Being a child does not protect him from the trans fat contained in the oil used to fry the meal he is eating. He is also at risk of heart attack, paralysis and stroke when they consume foods high in trans fat, according to Dr. Charles.

”Our fear is for those who have a family history of all these diseases and those who are 40 and above. It is now becoming common compared to the past, children are having heart-related diseases; we now have young people having heart attacks.”

A public health specialist and a former consultant on the WHO national project on Non-Communicable Diseases Interventions, Bridget Nwagbara, highlighted in a 2021 report that “in the past, it was unusual for young people in their twenties to have cardiovascular diseases but what we see now is young people with these diseases and eating healthy diets is still not a priority”

Another roadside food vendor who simply gave her name as Mrs Danjuma sells fried yam, puff puff and akara within the Yusuf Dan Tsoho Memorial Hospital in Kaduna. She also reuses her oil for all the meals she prepares just like other vendors around the area.

Suya is another very commonly eaten roadside food that Usman sells at the popular Wuse Market in the heart of Abuja. He said cooking oil is an ingredient that adds flavour to the meat. But how healthy is the cooking oil he uses?

Usman and his colleagues at Wuse Market prepare Suya meat for sale. Photo credit: Adesola Ikulajolu

The oil used by Usman in preparing his suya is mixed with another ingredient – “kuli kuli” which according to him gives it a different taste and aroma.

Usman took this reporter to an area within the market filled with numerous unbranded oil in plastic bottles displayed on a counter. It is from here he buys to use at ₦600 for an unbranded 35cl plastic bottle. It is cheaper than the 1litre branded oil that costs between ₦2000 and ₦3000.

Unbranded oils in plastic bottles are displayed on the counter at Wuse Market in Abuja where Usman purchases his ‘mixed’ suya oil. Photo credit: Adesola Ikulajolu

Analysing Sample Results

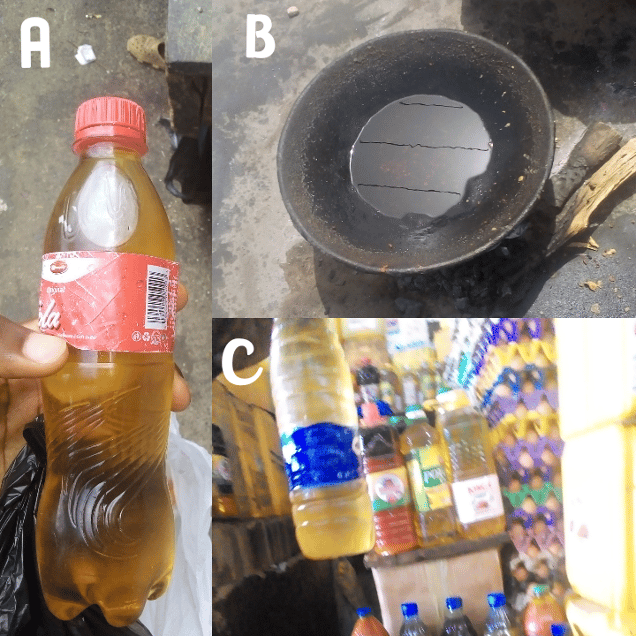

Three samples were tested at the Federal Institute of Industrial Research (FIIRO) laboratory, Lagos State for trans fat content. The samples: suya oil (sample A) collected from Usman at Wuse Market in Abuja, the akara oil (sample B) extracted from already prepared akara (simultaneously used in frying yam and puff puff) by Mama Ibo in Kano and unbranded oil (sample C) bought at the market without labelling.

Pictorial view of the three oil samples tested at FIIRO laboratory in Lagos. Photo credit: Adesola Ikulajolu

The test was carried out using the Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) method of analysis using the Gas Chromatograph Mass Spectrometers (GCMs) instrument which is generally used to analyze small, relatively equal compounds, identify different substances within a liquid or volatile sample and are widely used in forensics, food safety, environmental monitoring, and petrochemicals. FAME is produced from vegetable oils, animal fats or waste cooking oils by rearranging the fatty acids.

From the analysis received, suya oil (sample A) contained the highest level – 81.13%- of total Saturated Fatty Acid (SFA) compared to akara oil (sample B) which had the lowest at 39.98% and branded oil (sample C) at 42.16% of total saturated fatty acid.

Suya oil sample which has the highest quantity of fatty acid is also higher in Elaidic acid (16.61%) which is a major trans fat found in hydrogenated vegetable oils and very bad for human health because it lowers good cholesterol in the body.

These are unhealthy fats already being consumed by the over 200 million Nigerians on whose tables lie unhealthy oils similar to that used in preparing roadside foods like suya, akara, masa, puff puff and fried yam, among other such commonly eaten foods.

Frequent consumption of these foods, cooked with such unhealthy oil “leads to accumulation of trans fat in the body and high saturated fatty acids are not healthy because they build up cholesterol,” said Mr Ojo Bayonle, a laboratory scientist at FIIRO.

Mr. Ojo warns that “oil should not be reused more than two to three times and if oil is fried continuously for about two hours, then it should not be reused for frying or cooking.”

With the rising cost of living, this is not easy advice for the likes of Mama Ibo, Mrs Dajuma or Usman to follow because the cost of purchase and profit supersedes health hazards. However, proper regulations of oil used in the country may help to checkmate this.

Gbemisola Bamgbade, a dietician at the Lagos State General Hospital strongly warned that consumers should limit their intake of trans fat “, especially in roadside foods, pastries and processed foods and replace them with high fibre foods like vegetables and fruits.” This, she said, will help reduce the risk of CVDs and other related diseases.

While dieticians like Bamgbade strongly advise consumers to “form the habit of reading food labels,” roadside foods do not come with any label. An investigation in 2021 also exposed false labelling on some major oil brands in Nigeria, showing the dangers of consuming them.

For consumers like Hussein and Sani whose focus is on what to eat rather than the safety of what is eaten; and vendors like Usman and Mama Ibo who aren’t concerned about the safety of the oils used in preparing their foods– this investigation has shown that neither the rich nor the poor are exempted from this danger.

Perhaps, a firm and consistent regulation will save more Nigerians from heart diseases compared to when there is no policy to the rescue.

Trans fat Policy And Awareness To The Rescue

In 2018, WHO called for the global elimination of industrially-produced trans fat by 2023, through its comprehensive ‘REPLACE’ plan. The plan has six goals which form this acronym. They are Review dietary sources of industrially-produced trans fat and the landscape for required policy change; Promote the replacement of industrially-produced trans fat with healthy fats and oils; Legislate or enact regulatory actions to eliminate industrially-produced trans fat; Assess and monitor trans fat content in the food supply and changes in trans fat consumption in the population; Create awareness of the negative health impact of trans fat among policy-makers, producers, suppliers, and the public; and Enforce compliance with policies and regulations.

Since REPLACE was launched in 2018, WHO pointed out that an estimated 2.4 billion individuals have been protected. Denmark became the first country in 2003 to introduce legislation banning artificial trans fats with countries like Canada, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, Sweden and Iceland have followed.

Compared to South Africa which enacted a TFA limit in 2011, in Nigeria, the agency with the mandate to ensure the safety, quality, efficacy and wholesomeness of food and other regulated products, NAFDAC has been slow in the implementation of REPLACE and four years after the launch, there is still a failure in achieving global best practice for eliminating TFAs.

Joy Amafah, the Nigeria In-Country Coordinator for Cardiovascular Health (CVH) Program, Global Health Advocacy Incubator (GHAI) said the implication of not implementing a trans fat policy would increase preventable disease and deaths.

“Sadly, the Nigerian situation is precarious. Nigeria is behind the 2023 timeline because it is yet to have a regulation that reflects our country’s realities. The government must continue to prioritize limiting the consumption of trans-fat and take deliberate actions. According to available records, more than 70% of our population pays for healthcare out of pocket. We must put the regulations in place to remove the burden of cardiovascular diseases due to the consumption of trans-fat,” Amafah stated.

Another Suya seller at Life Camp, Abuja where he is preparing for the day’s sale. Beside him is the oil he uses to prepare his suya. Photo credit: Adesola Ikulajolu

NAFDAC, in 2019 released two drafts on ‘Fats and Oil Regulations 2019’ and Pre-packaged Food, Water and Ice labelling Regulations 2019 for public scrutinization which Edwards revealed is now in the “process of gazetting” after the finalised draft approved by NAFDAC Governing Council was returned to the Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH) on the 28th April, 2022.

The regulation is expected to apply to all foods containing fats and oils that are manufactured, imported, exported, advertised, sold, distributed or used in Nigeria highlighting that “no person shall manufacture, package, import, export, advertise, distribute, sell or use packaged fats and oils in Nigeria unless it has been registered in accordance with the provision of these Regulations.”

Currently, there is no legislation in Nigeria on the control of trans fats and delay in the passage of the draft regulation into law or failure to set up global best practices to protect the public from trans fat consumption puts Nigerian consumers at risk.

Organisations like CAPPA, the Network for Health Equity and Development (NHED), GHAI with many others have come together to raise a concern about the health risk in consuming transfat through the #TransfatFreeNigeria campaign.

Amafah highlighted that “if oils in the market are safe by being trans-fat free, the people won’t have to worry about their favourite foods which is why it is best to focus on the way forward to get the regulations to be gazetted by the government and enforced.”

While the process to enact the 2019 Fats and Oil Regulations is currently slow in Nigeria due to cumbersome processes and bureaucracies, FMoH National Coordinator for Food Safety and Quality Programme, John Atanda in a recent presentation said the department of of Food and Drug Services of the ministry has mapped out strategies to ensure the speedy gazetting of the process. But is this enough?

The Director of Food Safety and Applied Nutrition Directorate at NAFDAC, Eva Edwards during a presentation at the journalism training on transfat reporting in Enugu organised by Corporate Accountability and Public Participation Africa (CAPPA), said that “Nigeria should not be left out in the regulations aiming to eliminate TFA since it has been enacted in many countries.”

She added that the reduction of TFA in Nigeria’s food supply requires strong commitments from all stakeholders and a need to launch a ‘Read The Label’ campaign to create awareness towards a healthier, more productive population. But these are words which experts said pose serious health concerns if not urgently implemented.

Unless the ‘Fats and Oils Regulations, 2022’ is gazetted, consumers like Hussein and Sani; roadside vendors like Usman, Mrs Danjuma, and Mama Ibo will likely have their meals prepared with cooking oils laden with trans fats; unhealthy for them and risk factors for heart-related diseases.

*This Investigative Report was supported by Corporate Accountability and Public Participation Africa (CAPPA) and partner, Global Health Advocacy Incubator (GHAI) under her #TransfatFreeNigeria Project and published with permission from the author.